Vol. 2, No. 1

2 May 2017

"With or Without Onions"

A Sketch of General Thomas C. McMackin, Legendary Innkeeper of the Old South

After the

Chickasaw Indians ceded the last of their lands – six million

acres – in north Mississippi to the United States in 1832, a

veritable boom ensued.

Investors and speculators poured into the Chickasaw country looking

for cheap land. The

center of this frenzy was the present day town of Pontotoc – just a

clearing in the wilderness, then – where the federal government

located its land sales office. There

being no inns or boarding houses, the immigrants camped while they

sought their opportunities.

Tents covered the wooded, red clay hills for miles around.

After the

Chickasaw Indians ceded the last of their lands – six million

acres – in north Mississippi to the United States in 1832, a

veritable boom ensued.

Investors and speculators poured into the Chickasaw country looking

for cheap land. The

center of this frenzy was the present day town of Pontotoc – just a

clearing in the wilderness, then – where the federal government

located its land sales office. There

being no inns or boarding houses, the immigrants camped while they

sought their opportunities.

Tents covered the wooded, red clay hills for miles around.

Meanwhile, Thomas Cherry McMackin, a 30-ish South Carolinian, operated what passed for a tavern in those days some 70 miles to the southeast in what is now Yalobusha County, Mississippi, but was then just wilderness. McMackin’s inn consisted of but a few upright poles stuck in the ground with hand split boards nailed to the sides topped with a crude roof. Even so, and even in that remote locale, “[I]t was the remark of all [his customers] that he was out of his true place, and that he was eminently qualified to preside over the largest hotels in the largest cities of the Union.” So esteemed was McMackin for his abilities and leadership that his frontier associates began to call him “General” despite the fact that his military experience was limited to havng been captain of a local militia company as a young man in South Carolina. The title stuck.

“General” Tom McMackin saw large possibilities among the tents that covered the Pontotoc hillsides and, in 1835, relocated to the vicinity of the government land office there. Before he even had a building, the General went to work serving the public, on one occasion feeding some 1100 persons in the open air. This was not just some rustic barbecue, but a real feast with, as one contemporary described it, “an abundance of delicacies, and a plentiful supply of champagne,” though “the sparkling beverage [had to be consumed] from tin cups!” Col. David Crockett may well have been in that crowd, for he spent part of the latter half of 1835 in Pontotoc selling horses before leaving for Texas and the Alamo.

Realizing a town would arise from all the land buying activity, the General devised a scheme to insure himself a central position in that nascent community. McMackin bought a 160 acre tract of land from one Lawacha, a Chickasaw Indian, for the then princely sum of $1000 and built a log tavern on it. Then, in a stroke of the genius for which he would become celebrated, he donated a sizable piece of property adjacent thereto for use as a town square. McMackin, using bricks and timbers fashioned on site, next built “an immense establishment, including comfortable hewed-log white-washed cabins, with brick chimneys, around a great square” for sleeping quarters for 300 men and “a vast dining room and tables,[in]which for months” would be fed 700 to 1000 persons. The remainder of his land he divided into lots and offered them for sale. Just as he had hoped, his lots, being close to his donated town square and his massive hotel, sold quickly. Within three months he brought in some $80,000 from his original investment and numerous businesses began springing up on the lots he had sold, including some 40 stores and, more interestingly, 23 groceries – grocery being the euphemistic name then applied to a saloon.

McMackin’s skills as a restaurateur, though, are what made his reputation. His dining hall was a thing to behold. Seventy five well-trained cooks and waiters staffed the establishment. Three long tables ran almost the entire length of the great log building with smaller cross tables at both ends. McMackin, a lean six footer, his hair long as was the fashion, habitually wore a suit and white apron. He stood straight and erect behind one of the cross tables, presiding over the meats, soups, and vegetable, while his wife, Lucinda, administered the opposite cross table loaded with desserts and beverages at the other end of the hall. Lamar Fontaine, who, as a boy, visited his grandfather in Pontotoc during the mid 1830s, once recalled the scene at McMackin’s at meal time.

“The guests were called to the meals by the beating of a musical triangle by” one of the waiters “who, while striking the triangle, with a sonorous voice would cry out, ‘Oh yes, oh yes, dinner [or supper, or breakfast, as the case might be] is now ready; walk in ladies and gentlemen, but children must wait till the next table.

“As the guests were seated, the general would flourish his carving knife, wring it loud across his glittering steel sharpener, and . . . cry out in a loud voice, ‘Oh yes, oh yes, here’s your beefsteak, rare and well done . . . . Here’s your ham, jelly and jam; biscuits beaten, hot or cold; with fresh butter; all kinds of vegetables, sweet potatoes, Irish potatoes with their jackets on and in their shirt sleeves, French fried, lyonaise or floating in cream; eggs boiled, scrambled, fried or poached in any style; four-storied puddings, tea, coffee, sweet milk, butter milk, brandy, wine, gin or beer at my wife’s end of the table.” Many years later, when asked why he shouted out the menu instead of having it printed, he said it was because many of his customers were members of the state legislature, and most of them could not read.

Somewhere in his announcements the General always worked in the words, “with or without onions,” which became his trademark. Whenever his name appeared in the press over the next four decades, and it would, many times, that signature phrase was ays included.

As the guests ate McMackin constantly floated among them, making certain that they were satisfied with their meals and offering more – at no extra charge – to all not yet sated. The foods rivaled the fare of the finest New Orleans restaurants of the day – salt- and freshwater fish, oysters, mutton, beef, and wines were regularly on the McMackin boards – an amazing accomplishment, especially when you consider that the nearest food suppliers were in Tuscumbia, Alabama, and Memphis, Tennessee, both over 100 miles from Pontotoc through a roadless, bridgeless wilderness. McMackin sent his own wagon trains to those cities to obtain the food and drink for his tables.

Many, if not most, of those the General sheltered and fed in Pontotoc were well-heeled investors looking not so much to get rich as richer. Times were indeed flush. Gold and silver brought in for the cash only land sales abounded to that point that kegs of coins were sometimes used as stools in Pontotoc businesses. One store floor collapsed from the weight of such a keg! Yet the General took no advantage of his customers’ prosperity or of his virtual monopoly on the innkeeping business in the region. Sharp dealing was not in the man’s nature. To the contrary, he made “every guest imagine himself the object of especial attention and benevolence” and sought “to make everyone happy about him.” He offered a bed, three meals, and a stable and provisions for a horse for but three dollars a day – less than $80 in today’s money! Even at those bargain rates McMackin often brought in $1000 to $2000 per day.

Despite his success, McMackin left Pontotoc in 1838 to open the Exchange Hotel in Memphis, which, its high standards notwithstanding, apparently was not a financial success. Two years later, still in Memphis, he launched the McMackin House, a “splendid restaurant,” according to Memphis Appeal editor Van Pelt, but, apparently, “too splendid” for Memphis. It, too, went under. After the General’s attempt to develop a horse racing track likewise failed, he left the Bluff City to return to his adopted Magnolia State for, as he once said, he was a “Mississippian, with or without onions.”

By 1844 McMackin was operating a tavern called Union Hall in Jackson, Mississippi, and “feasting the epicures of" that young city on, among other things, “drum from the Pearl” River and “fine venison from . . . Scott County," all, of course, “with or without onions.” The General’s Jackson career, though, proved short-lived. He was there long enough to serve as sergeant at arms at the state Democratic convention in 1845 and to lose a bid for that same post with the state legislature in January 1846. It was during his Jackson tenure that about the only criticism of the General was recorded: a cantankerous capital correspondent for a Holly Springs, Mississippi, newspaper, called him "that eternally babbling caterer of soup and sausages."

The General moved on to Vicksburg in 1846 to operate an inn there. Vicksburg became as close to a permanent home as McMackin would ever have. McMackin and his hotel quickly became institutions in that city. When the Vicksburg Hibernian Mutual Benefit Society observed St. Patrick's Day with a celebratory banquet in 1847, its "sumptuous dinner" was held, of course, at "that well known Hotel kept by the prince of landlords, Gen. McMackin." When the drinks were poured, McMackin proposed this toast: "The Irish forever, with or without onions."

Although in his 60s when the Civil War broke out, McMackin accepted an appointment as a military “transportation quartermaster,” serving in Vicksburg throughout the siege of that city. After the war he returned to business as proprietor of the Prentiss House hotel in Vicksburg. From there we have one of the last reports of his marvelous talents as a maitre d’hotel, this one from a writer in 1871 who signed his name only as “Guest”:

“There stood the old veteran and issued his orders, as I heard him give them in the midst of the Chickasaw wilderness, more than thirty years ago; his eye is undimmed and his natural voice unabated . . . , strong, clear and musical and animating everything about him.” As in his glory days, his “large dinner-room was crowded with eaters, from the north, south, east and west, reveling upon the eatables and drinkables of all climes.”

McMackin’s “character,” wrote Guest, “. . . electrifies a wide sphere about him with his own cheerfulness and energy.” Memphis Appeal editor Henry Van Pelt once lamented his city’s loss of McMackin to Mississippi. To have kept him in Memphis, he contended, would have done more to promote commerce there than paving any six of its dirt streets.

The General’s excellent fare and the “benign effects of [his] speech and countenance” certainly worked marvels among his customers, for at his tables in Vicksburg, a city so recently the scene of bloody partisan conflict, “Federal officials, in blue, with Confederates in grey, Northern merchants and Southern planters, oblivious of all differences, . . . peacefully mingled, and [were] forgetful alike of the past and indifferent to the future, . . . only intent upon the one object before them, which was to fill themselves to the throat, in obedience to the orders of the General, whose voice was heard above the din of steel and crockery, the popping of bottles and clatter of glasses.

“’Oyster soup, soup without oysters and oysters without soup; fried fish, boiled fish, Mississippi trout, fish from the rivers and fish from the sea; roast beef, boiled beef, toast mutton, boiled mutton, mutton with caper sauce; beef and mutton, with and without onions; mutton and lamb, with jelly and jam; hot boiled ham, cold ham; hot shoat, cold shoat; roast turkey; fouls roasted, baked and fried; potatoes mashed and potatoes whole, potatoes baked and potatoes fried upon one side, and potatoes fried upon the other side, with celery, peas, cabbage, turnips and vegetables and sauces of all sorts. Gentlemen and ladies, help yourselves. I hope you are well supplied. Oh it does my soul good to see you happy! Waiters, hurry up the dessert. Cranberry tarts, apple pie and pies of all kinds, plum pudding, and cold potato pudding for those that are in love! Fruits and nuts from all countries, and wines from all countries, and wines from Italy, Germany and France; wines from the Rhine and wines from the Po; wines from Portugal, and wines from Ohio. Gentleman and ladies, we are an immense people, in spite of war.’”

Little is known of McMackin after 1871. He left the inn-keeping business temporarily due to a severe illness, but was back at work in 1873. He was in Hot Springs, Arkansas, in 1875. Whether he sought the curative powers of the supposedly medicinal springs there, or whether he was running one of the town’s many spas, we cannot be sure, but he died there that same year. General Thomas C. McMackin is believed to be buried near his daughter in Greenwood Cemetery in Jackson, Mississippi, in an unmarked grave.

“His honesty and generosity, in spite of his great energy and industry, have prevented him from hoarding what he has made,” a friend once said of him, “and he never can be rich. The more he makes the more he spends to add to the pleasure of his guests. . . . For thirty-five years he has been the faithful servant of thousands of our moving multitudes, and a great benefactor to the country.” As an innkeeper, that writer insisted, “No one has ever rivaled him, and we shall never see his like again.”

Clearly,

McMackin’s was an “immense” life, “rare and well-done, with or

without onions.”

Vol. 1, No. 3

10 October 2016

Mississippi Delta the Biblical Garden of Eden?

During my seemingly never

ending research on the Old Delta I

recently came across an article that appeared in a number of

newspapers in 1907. “Says Eden Was in Mississippi,” reads the

headline. A subhead explains further: “Kansas Scientist Claims that

Yazoo County was the Birthplace of Man.”

I read further: Not only had a “Professor Clinton McMickle” determined that the Garden of Eden had been located in Yazoo County (I’m sure Willie Morris would have agreed with that), he placed the site of original paradise precisely at the location of the property of Major W. A. Henry, who was at that time a well-known lawyer and planter in Yazoo County. Major Henry’s place was approximately seven miles south of Yazoo City near Lake George and the present site of the Panther Swamp National Wildlife Refuge.

I began combing the internet for more on this Kansas academic. It didn’t take long to discover that he was neither a professor nor a scientist. Quite to the contrary, McMickle was an Indiana-born Kansas farmer – one of the early settlers of Cherokee County in that latter state. While McMickle was a Union veteran of the War Between the States (Co. 2nd Iowa infantry) and saw action under Sherman in, among other places, South Carolina, it is doubtful that he ever saw much of the inside of a schoolhouse.

Despite his lack of formal education, McMickle had an active, if not especially critical, mind, and, by his later years had acquired a reputation among his neighbors and fellow citizens as proficient in astronomy, geology, and physics. He was interested, especially, in archaeology, and had excavated Indian mound graves in Missouri. McMickle also became known for his letters to the local newspaper in which he set out his theories and predictions. The editor, perhaps a bit facetiously, referred to him as the “Sage of Chetopah,” Chetopah being the small town closest to McMickle’s log cabin farmstead.

McMickle’s scientific and archaeological reading, perhaps influenced by his 7th Day Adventist faith, led him to theories about man’s origins that blended Greek mythology with the Genesis creation and flood narratives. Poseidon, the sea god of the Greeks, he contended, was one and the same as Adam, the Biblical progenitor of the human race. Eden, he posited, was within the boundaries of the Atlantis of Plato’s legend. McMickle suspected that a string of Indian mounds stretching from northeastern Arkansas down to the south Texas coast formed the western limits of Atlantis. He was more certain that “[t]he northern boundary [was] marked by a line of forts in Tennessee,” with “[t]he best preserved” of them being “on the big Harpeth River.” That northern boundary, he said, “crossed the Mississippi a few miles above Belmont, Mo.”

By the time he reached his late 70s, if not sooner, McMickle had amended his 1907 hypothesis somewhat. Rather than Eden being located in Mississippi, he decided that the entire U. S. was coextensive with the Biblical Land of Eden. The Garden of Eden, which he understood as a smaller expanse of real estate than the entire Eden, was not just Yazoo County, but the entire Delta!

The Garden of Eden, McMickle wrote, was identical to the Atlantis written of by the philosopher Plato. According to Plato, McMickle said, the story of “The Lost Island of Atlantis” had been “translated from the Egyptian by Solon, 6th century B. C., and from an older tongue to the Egyptian.” Noah, who, according to McMickle, spoke Sanskrit, the only “older tongue” than “the Egyptian” was the original author of Plato’s account of the lost civilization of Atlantis. When the Deluge came, Noah built his ark right there in the Mississippi Delta, the gopher wood of which the Bible says Noah constructed that vessel being none other than the Delta’s ubiquitous bald cypress! Once Noah and his family entered the Ark and the flood waters rose, the currents carried them to the mountains of Ararat in Armenia – quite a ways from their Delta home

There was no doubt in McMickle’s mind that the Delta was both the Garden of Eden and Atlantis. Like Atlantis, he noted, the Delta was an Island, bounded by the Mississippi to the west, the Yazoo and its tributaries to south and east (and much of the north), and on the north by the Yazoo Pass, connecting Moon Lake (which adjoined the Mississippi in high water) with the headwaters of the Yazoo system. Yazoo Pass, by the way, McMickle said, was dug by labor conscripted by Seth, the son of Adam. The dimensions of the Delta, he said, were the same as those of Atlantis. Too, many of the landmarks mentioned in Plato’s tale still existed in the Delta, he contended, though they were buried in dirt and “talus” – geologic debris – from the flood.

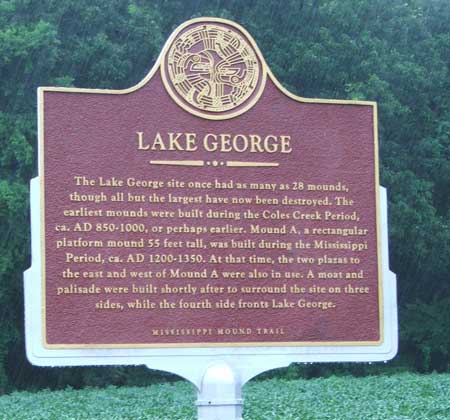

According to McMickle, mounds near the site of the Henry Plantation (mentioned at the outset) in Yazoo County, which are known to 21st century archaeologists as the Lake George Group for their proximity to that body of water, marked the location of the ancient city of Poseidon. That city, said McMickle, included a solid gold temple built by Adam (Poseidon). [Note: some of the Lake George Mounds can be seen today along Mississippi Highway 433 between Satartia and Holly Bluff.] Nearby, he also believed, could be found the ancient cemetery wherein reposed the bodies of our first parents. All of this, of course, lay buried far beneath the earth’s service due to cataclysmic flooding that occurred on November 8, 2339 B. C. due to an unprecedented conjunction of Jupiter, Mars, Venus, and Mercury that exerted an unprecedented gravitational pull on the sun with disastrous effects on the earth and its inhabitants. The Temple remained, McMickle was confident, beneath the Henry plantation. He hoped “to organize a stock company for the purpose of making extensive excavations.”

In 1907 McMickle wrote Mississippi governor James K. Vardaman a letter laying out his theory and requesting a map of the Delta. Vardaman sent no map but put McMickle in contact with Lamar Fontaine. Born in the Republic of Texas and named for its second president, Fontaine was at one time or another a Comanche captive, poet, sailor, mercenary, Texas Ranger, Confederate soldier, and songwriter. After the Civil War he settled in the Mississippi Delta where he was a civil engineer, surveyor, and friend of the protagonist of my book The Bear Hunter, Robert Eager Bobo.

McMickle inquired of Fontaine concerning certain features of the landscape at the Henry plantation, including but not limited to the existence of certain mounds. According to contemporaneous news accounts, Fontaine confirmed the existence of the features and, accordingly, became convinced of the accuracy of McMickle’s theories. Fontaine, who was known to be a master of the practical joke, probably was just playing along [Fontaine makes a cameo appearance in The Bear Hunter, in fact, precisely because of his penchant for the prank]. In his book, My Life and My Lectures, published the following year, Fontaine did express some views on the builders of the Indian mounds similar to McMickle’s, but Fontaine contended the North American Arctic was the site of the Garden of Eden, and that the first post-Eden civilizations developed in the Andes Mountains of South America.

If McMickle ever visited Mississippi, there is no record of it. At least as late as 1923, though, he continued to hold to his theory that the Mississippi Delta was the site of the Garden of Eden.

Clinton McMickle, the Sage of Chetopah,

Kansas, died in 1931 in Lola, Cherokee County, Kansas. May he rest

in peace.

Copyright 2016 James T. McCafferty

Vol. 1, No. 2

21 July 2016

HOWLING IN THE DELTA

Fewer sounds were more familiar--or more chilling--to the 19th century southern pioneer than the high, lonesome wail of the wolf. In her marvelous autobiography, Trials of the Earth, backwoods logging camp manager Mary Hamilton mentioned wolves at least a half a dozen times and noted that, to a person lost in the woods at night, their howling could almost bring on insanity. Even wildlife writer Ernest Thompson Seton, who normally exhibited the professional naturalist's disdain for myths and old wives tales, found in the wolf's howl something that "never fails to affect me personally with a peculiar prickling in the scalp that I doubt not is a racial inheritance from the stone age."

The wolf's wild, weird serenades must have been especially unnerving to the pioneers of the Deep South. The moss-draped forests and dense canebrakes covering Dixie during the early days of settlement surely were mysterious enough without the added discomfiture of the wolf's banshee-like baying. Mississippi blues singer Howling Wolf, né Chester Burnett, by one account took his nickname from the wolf stories his grandfather would frighten him with as a child. Still, some found a strange, romantic comfort in the wild canine's haunting nocturnes. "The howling of the wolf" wrote early Delta resident and later Mississippi governor Benjamin G. Humphreys, for whom Humphreys County was named, "was the lullaby of my infant slumbers."

as a boy in Mississippi's Coahoma and Washington counties in the 1960s and 70s I heard tales of wolves that supposedly roamed the Delta woods between the Mississippi River and levee even then. I read anything I could get my hands on about wild canids in the South and was convinced that the wolves behind the levee were red wolves. Not nearly as well-known or widely distributed as the gray wolf ( Canis lupus ), the red wolf (Canis rufus ) once roamed America's woodlands from Texas to the Carolinas, and from the Gulf of Mexico to the Ohio River Valley.

Despite his name, rufus historically came in a wide range of colors from buff to black and just about every shade in between, including the reddish phase from which the species took its name. Typically weighing from 40 to 80 pounds, the red wolf averaged only about two thirds the size of his gray cousin. Like the gray wolf, the red had a longer, more "wolfish" muzzle than the comparatively snub nosed coyote. The Red, though, was less sociable than the larger gray canine, favoring small hunting groups to the large packs associated with Canis lupus.

The red wolf, most sources say, rarely tackled large prey, preferring to make his meals of rabbits and small rodents. Mississippi writer J. F. H. Claiborne (1809-1884), though, once watched a pack of south Mississippi wolves bring down a full grown whitetail buck. The red wolf was always a shy creature, and history, according to most authorities on the subject, is virtually devoid of red wolf attacks on man. Nonetheless, the first settlers in the South superimposed their preconceived notions about wild canines on the relatively harmless red wolf. Records of this fear come from as early as 1791 when naturalist William Bartram, while traveling in Florida, noted that the wolves "assemble in companies in the night time, howl and bark together, especially on cold winter nights, which is terrifying to the wandering bewildered traveller." Some travelers may have had reason to be afraid. Coahoma County, Mississippi’s, Robert Eager Bobo, premier bear hunter of 19th Century America and acknowledged expert on the Mississippi bottomland wilderness of the post Civil War era, once told of a man he knew who was treed by a pack of wolves and broke his empty rifle trying to club them away before he was finally rescued by a group of hunters. Apparently no one bothered to tell those wolves that they were not a danger to humans!

The red wolf's unfortunate habit of stealing an occasional pig or calf (Mary Hamilton reporting losing young cattle to wolf depredations) did little to disabuse early Southerners of their misconceptions about these reclusive denizens of the woodlands.

State and local governments placed bounties on wolf scalps, and farmers and ranchers trapped, poisoned, or shot the animals at every opportunity. By the late 1800's this relentless killing, together with a dramatic increase in the destruction of southern woodlands, had greatly diminished the red wolf's original range. Over most of the South, the howl of the red wolf was already but a shadowy memory. Still, they lingered on in parts of their former range, including Mississippi, and still they were targets of indiscriminate and often government sponsored killing.

As

if human

persecution was

not trouble

enough

for this

beleaguered species,

the red wolf

faced a threat from

canine quarters as well.

While the wolf's home territory was shrinking, the smaller,

more adaptable coyote actually was expanding

its range, in

many cases overlapping that

of the red wolf.

As early as 1920, the two species began crossbreeding,

producing hybrid offspring, which furthered endangered the

red wolf's chances for survival.

Killing both species continued to be

considered a necessary means of conservation of game animals like

deer and turkey. Pearl River County, Mississippi, like

many counties throughout the wolf's range, in 1938 offered a $25

bounty for each wolf or coyote killed or captured. That same

year, an article in Mississippi's state game and fish magazine

announced an "eradication drive" aimed at "coyotes and timber

wolves" in south Mississippi indicates that the range of the two

predators were overlapping even then in the Magnolia State.

By 1962, coyote-wolf hybrids had replaced red wolves

throughout most of the

latter's range,

and only a few hundred supposedly genetically pure members of the

Canis rufus breed survived.

Mississippi's state game and fish magazine

announced an "eradication drive" aimed at "coyotes and timber

wolves" in south Mississippi indicates that the range of the two

predators were overlapping even then in the Magnolia State.

By 1962, coyote-wolf hybrids had replaced red wolves

throughout most of the

latter's range,

and only a few hundred supposedly genetically pure members of the

Canis rufus breed survived.

Those few hundred may not have been as genetically pure as once thought. Recent studies indicating substantial coyote genes in the red wolf's make up suggest what many biologists have long suspected may in fact be the case: that the historic red wolf was not an actual species so much as a population of coyote/gray wolf hybrids. Other studies suggest that there was at one time a separate red wolf species, but that it long ago picked up substantial coyote DNA from crosses with that animal. Interestingly, the coyote population of the Southeastern states seems to have picked up some wolfish genes along the way – a black phase coyote, very rare in the west, is not uncommon in the southeastern coyote population. The black genes quite likely came from Coyote/red wolf interbreeding.

Whether they represented a true species or were coyote/wolf hybrids, a tiny remnant population of red wolves made a last stand in the swampy, Gulf Coast country on the border of Texas and Louisiana, a desolate domain of muskrats, alligators, and armadillos. This semi-tropical environment was, at best, marginal wolf habitat, plagued with heartworms, hookworms, and other canine parasites that shortened the lives of mature wolves and caused high mortality rates among their pups.

The future held little promise for the red wolf.

Then, in 1973, the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (U. S. F. & W. S.) formed the Red Wolf Recovery Team with the goal of rehabilitating this remaining rufus population. The wolf’s numbers, though, were too low to be viable in the wild. It quickly became apparent to the Recovery Team that the species’s only chance for survival was a captive breeding program.

Trappers were set to work rounding up as many so-called pure red wolves as possible, that purity determined largely by looks and size. Most were sent to the Red Wolf Captive Breeding Program at the Point Defiance Zoo in Tacoma, Washington. By 1980 the trappers were finding no more specimens that appeared “genetically pure.” Isolated individuals remained, no doubt, but, for all practical purposes, the red wolf was extinct in the wild by 1981.

Even as the last wolves were dying in Louisiana and Texas, however, the 40 animals captured by the recovery team were bearing young at Point Defiance and other zoos around the country. Too, the U. S. F. & W. S. was making plans to begin the first attempt ever to reintroduce a species extirpated from the wild to its native range.

That was not to be easy. The new home for these rare canines had to be large enough to accommodate their tendency to roam, wild enough to keep contact between the wolf and man (and man's domestic animals) to a minimum, and totally free of gene pool polluting coyotes.

Project leaders determined that the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, located on a Dare County, North Carolina, peninsula covered with 170,000 acres of coyote-free coastal marsh and forest offered the perfect situation for the project. The site of Sir Walter Raleigh's Lost Colony of Roanoke Island (whose inhabitants disappeared without a trace in 1587) just a few miles to the east, added a touch of appropriate irony to the selection of the refuge as the home for America's most endangered mammal.

Next, biologists selected four male/female pairs of wolves from the Point Defiance Zoo group. In November 1986, they were delivered to the Alligator River refuge and eventually released into the wild. One pair was placed for a short while on Horn Island off the Mississippi Gulf coast but was subsequently removed because of frequent human visitation there.

The Alligator River group prospered, growing to over 100 animals. That number, now, has declined to between 50 and 60 wolves, due in part to cross-breeding with the coyotes that showed up at the refuge in the early 1990s.

The coyote has contributed to the red wolf's recent decline for another reason. Humans untrained in wild canid biology often have not been able to distinguish between the two predators. For instance, Coyotes have been documented in Mississippi since at least the 1930s. Until the late 1970s or early 1980s, however most Mississippians who happened to see a coyote would likely identify it as a wolf. For example, when I was in high school in New Albany, Mississippi, around 1971, the town paper carried a photo of a local farmer with a "wolf" he had killed in one of his fields. The "wolf" didn't look to weigh over 30 pounds and was plainly a coyote. I also suspect those "wolves" I often heard about in the Delta as a boy were coyotes, as well. Now, though, the coyote is far more familiar to hunters than is the wolf. No doubt some of the Alligator River red wolves have been shot by persons who thought they were killing coyotes.

The release program, by any measure, has been something less than a total success. Some biologists even believe that it is a futile effort to save what may not even be a real species. Still, real species or hybrid, the red wolf was once a part of the Deep South wilderness experience.

Despite their limit success in the wild, red wolves continue to do well in zoos. A pair at the Jackson, Mississippi, zoo, produced eight pups less than two years ago. You can see the Jackson Zoo's red wolves almost any day you care to visit. It is unlikely, though, that the red wolf will ever roam wild in the Mississippi woods again. Those of us who long to hear the eerie howl of the wolf drifting through the canebrake as Benjamin Humphrey did in his childhood so long ago, at least for the foreseeable future, must be content with the occasional yelping of coyotes.

Vol. 1, No. 1

15 June 2016

Welcome to the first installment of the Canebrake Pilgrim Blog. The purpose of this blog, as its subtitle implies, is primarily to explore the history of the American South -- especially as that history pertains to the outdoors, and particularly as it pertains to the Lower Mississippi Valley. I am a lifelong resident of Mississippi and spent most of my formative years in that state's Delta Country. I have been interested in and often written about those topics and have created this website as an outlet for my writing. As the owner and author of this Blog I reserve the right to consider other subjects from time to time. I plan Blog entries fairly regularly but at this time plan no particular schedule.

There are some standard pages to the site: a Home page, which contains a bit of an introduction to the site; a Contact page, which provides contact information; and a Coming Events page, which calendars my appearances, book signings, and other events related to my books or the purposes of this site.

There are also some pages that, really, are the main reasons I began this website: the Canebrake Hall of Fame and the Canebrake Archive. The Hall of Fame profiles significant historical characters -- at this point I am limiting it to persons connected with the Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana Delta lands prior to 1920. Some of these persons may be familiar to you; others may not. All deserve to be remembered.

I am particularly pleased with Canebrake Archive. It is hoped that this website will encourage others to research and write on history of the outdoors in the Lower Mississippi Valley, as well. Far too little has been done in that area, and many of the historical sources for such research are obscure or unavailable in even the best libraries. In hopes of assisting researchers and those just interested in outdoor history, the Archive provides links to online sources as well as some sources not available elsewhere on the web.

Finally, the website offers for sale books I have written: The Bear Hunter: The Life and Times of Robert Eager Bobo in the Canebrakes of the Old South and two children's book, Holt and the Teddy Bear and Holt and the Cowboys. Others are in the works.

I have been gratified by the reception of The Bear Hunter: The Life and Times of Robert Eager Bobo in the Canebrakes of the Old South. If you are not familiar with it, take a few minutes to check it out.

I hopes to hear from visitors to and readers of this site. Please do not be shy about sharing your insights, stories, suggestions, etc., concerning this website and the subjects to which it is dedicated.

But let us not delay! The party is gathered; the horses are champing at their bits; the dogs are spoiling for a fight; the hunters are sounding their horns. It is time to ride!